A strong union

In their endeavor to supply the beverage industry from a single source wherever possible, from the 1980s onwards the machine manufacturers underwent a series of mergers and acquisitions. The result was what’s now KHS.

As early as in the 1960s and 1970s the spirit of consolidation began to waft through the production halls of the beverage machine manufacturers which were to eventually form KHS. In 1966 the Enzinger-Union-Werke in Mannheim acquired Noll Maschinenfabrik in Minden. Just three years later the expanding company entered into an extensive cooperation with the Seitz-Werke in Bad Kreuznach under the motto of “stronger together”. These first steps already aimed to cater for the customer requirement for supply from a single source – insofar as this was possible. In 1977 the Klöckner-Werke in Duisburg, the fourth-largest steel company in Germany, procured a quarter of the shares in Holstein & Kappert in Dortmund, becoming the majority shareholder just two years later and concluding a domination and profit-and-loss-transfer agreement.

New sources of income

In the meantime the slump in exports was also being felt in the German mechanical engineering industry, when 500 jobs were lost at Holstein & Kappert in Dortmund between 1983 and 1985, for example. In order to safeguard the competitiveness and economic survival of the company the merger became all the more important and Klöckner did all it could to secure its event. The packaging sector was thus outsourced to a separate company, H&K Verpackungstechnik GmbH, and four fifths of subsidiary Rosista, which made valves at the branch plant in Unna, were sold to the British APV Group which at the time had a turnover of €1.5 billion and about 14,000 employees. Holstein & Kappert had entered into a long-term cooperation with the British which governing the licensed manufacture and sale of plate heat exchangers on the German market at the end of the 1920s.

At drinktec-interbrau in Munich in 1993 the new KHS company presents itself to the public for the first time: the clothing sported by the booth personnel specially tailor-made for the occasion causes quite a sensation.

In 1986 the German Federal Cartel Office approved the merger of Holstein & Kappert and SEN. A little later Klöckner announced that it was now the majority shareholder of SEN – without permission from the minister, the application for which Klöckner had withdrawn in the meantime. In the following year Holstein & Kappert was turned into a corporation. The SEN shareholders’ meeting approved the merger agreement with a big majority; a few of the shareholders, however, who had possibly hoped for a higher dividend from the transaction, filed a lawsuit contesting the decision and managed to prevent the merger from actually coming to pass for many years to come.

The reason why the Klöckner-Werke now entered the field, which in the 1960s had already addressed a completely new area of business with plastics processing and film manufacture through Klöckner Pentaplast in Montabaur, was the emerging steel crisis. Diversification was the order of the day and the heads of the mining group had recognized how much growth potential the manufacture of machines for the international beverage industry held. When in 1982 the Enzinger-Union-Werke and Seitz-Werke also officially merged to become Seitz Enzinger Noll Maschinenbau AG (SEN), presenting Holstein & Kappert with some strong competition, the Klöckner-Werke again stepped in: the Duisburg concern acquired 24% of the share capital of SEN and the option of later picking up a further 26% which was initially held in trust by a bank. It was soon obvious that Klöckner aimed to effect a merger between former competitors Holstein & Kappert and SEN. When in 1984 the German Federal Cartel Office refused to allow the acquisition of the majority of shares in SEN, the Klöckner-Werke sought ministerial approval from the Federal Ministry of the Economy in Bonn.

Manfred Rückstein, head of Corporate Communication

The KHS brand

At Holstein & Kappert from 1966 to 2015, then at KHS and head of Corporate Communication from 1991, with a three-year intermission working for a main competitor: communications expert Manfred Rückstein, now 68, looks back on some eventful years.

How did the name “KHS” evolve for the merger?

This was an invention of the supervisory board made up of the initials of the group parent company and the two partners. Because the designation “KHS” couldn’t be trademarked in its own right we had to develop a logo made up of a word and a graphic. The first ideas with a stylized arrow pointing into a box then turned into the present logo we still use today.

What was the biggest communicative challenge?

We had to make it clear to our customers, who for decades had been loyal to either the one or the other brand, that the products from Bad Kreuznach, Worms and Dortmund were now all on an even par. We also had to convince our employees that we weren’t selling old wine in a new box but that a totally new company had been formed which wanted to move further forward.

How long did it take for the company’s new identity to be formed?

It took a few years to implement the process – which in some areas is still ongoing. You can see this in Bad Kreuznach, for example, where some still consider themselves to be Seitz workers, or in Kleve with the Kisters people. This isn’t an issue for new employees – they only know KHS.

How was the new brand received by the market?

We had our first major appearance as KHS at drinktec-interbrau in Munich in 1993. We had our booth personnel, over 300 of them, dress in bright blue jackets and red ties or red skirts and blue blouses – in our new company colors. Many of the more fashion-conscious gentlemen were so unhappy about this that they deliberately gave the wrong information when asked for their clothing size to avoid having to wear the “colorful uniform”. We had some jackets in reserve, however, and could solve part of the problem by getting people to swap sizes. We also quickly had 20 extra jackets made from the specially dyed fabric. The result was a real sensation which made it clear that just one single company was exhibiting at the trade show. Our customers didn’t have to spend a long time trying to find a contact and almost every TV report on the show was filmed at the KHS booth.

What other measures did you use to support the merger?

The key factor was the launch of our standardized brands – in the face of opposition from some of our older colleagues who would’ve preferred selling their products under the old names. A high-ranking brand developer assisted us at the time. The result was a flexibly extendable system of nomenclature which is still in use today, namely the “Inno” prefix – in 1993 innovation wasn’t a word which was used as much as it is now.

Useful additions to the portfolio

Downwind of the turbulences of corporate law, the affected companies stoically continued to focus on their actual business. For Holstein & Kappert this meant founding H&K/ETI-TEC in Erkrath in 1987, for instance, whose employees were highly-qualified labeling machine specialists known to the market. This subsidiary made useful additions to the range of products sold by the Dortmund parent company which was now also able to give its customers’ packaging an identity. Another subsidiary charged with various special process engineering tasks, H&K Prozesstechnik GmbH, was also founded during this period.

In the meanwhile the battle for the merger continued: the APV Group had procured 40% of the shares in SEN and was negotiating with Klöckner on the full takeover of the company. In an interview for the weekly “Die Zeit” newspaper its chairman of the board Herbert Gienow contradicted APV chairman Sir Ronald Mclntosh, who had claimed that the merger would be to the detriment of the SEN workforce: “The possible forty million marks saved by the merger will not be gained by shutdowns and a reduction in personnel but by a forward strategy which envisages the creation of focused manufacturing centers, product standardization and the development of new sales markets.” Gienow promised that “production sites will not be endangered but strengthened. The workforce will be increased.” In 1988 APV threw in the towel and sold its SEN shares to the Klöckner-Werke which now owned 90% of the company merger. At the same time APV acquired the remaining 20% Holstein & Kappert still held in Rosista for 3.5 million marks.

In 1990 a domination and profit-and-loss-transfer agreement was drawn up with Klöckner Mercator Maschinenbau and SEN. Even if the legal hurdles had not yet been fully removed, the merger between SEN and Holstein & Kappert began to take shape on an operative level. A management board was set up for both partners containing the same members and divisions and packaging machine manufacture for both companies was united in the company named KHS Verpackungstechnik in Worms.

Severe cuts

At the end of 1992 Klöckner was forced to apply for a settlement due to excessive debts with the local court in Duisburg to avoid bankruptcy and initiated a restructuring process which involved a number of severe cuts.

In 1993, after a legal dispute lasting six years, the Federal High Court of Justice dismissed the legal challenge to the merger resolution of 1987. Holstein & Kappert and SEN finally merged to form Klöckner Holstein Seitz (KHS) AG, with nothing now preventing their first joint appearance at the drinktec-interbau trade show in Munich. The first years of the new company saw high job losses – also due to the difficult phase Klöckner had recently gone through: of the 3,500 employees in the three remaining factories about 1,000 had to leave the company, with 290 laid off at the headquarters in Dortmund alone. In 1995 huge losses led to the closure of KHS Iberica, KHS’ subsidiary in Spain, and KHS Carmichael, the Scottish specialists for wrap-around labeling.

KHS is headquartered in Dortmund, where the old Holstein & Kappert factory erected in 1925 on Juchostrasse had a modern extension added to it at the start of the 1990s.

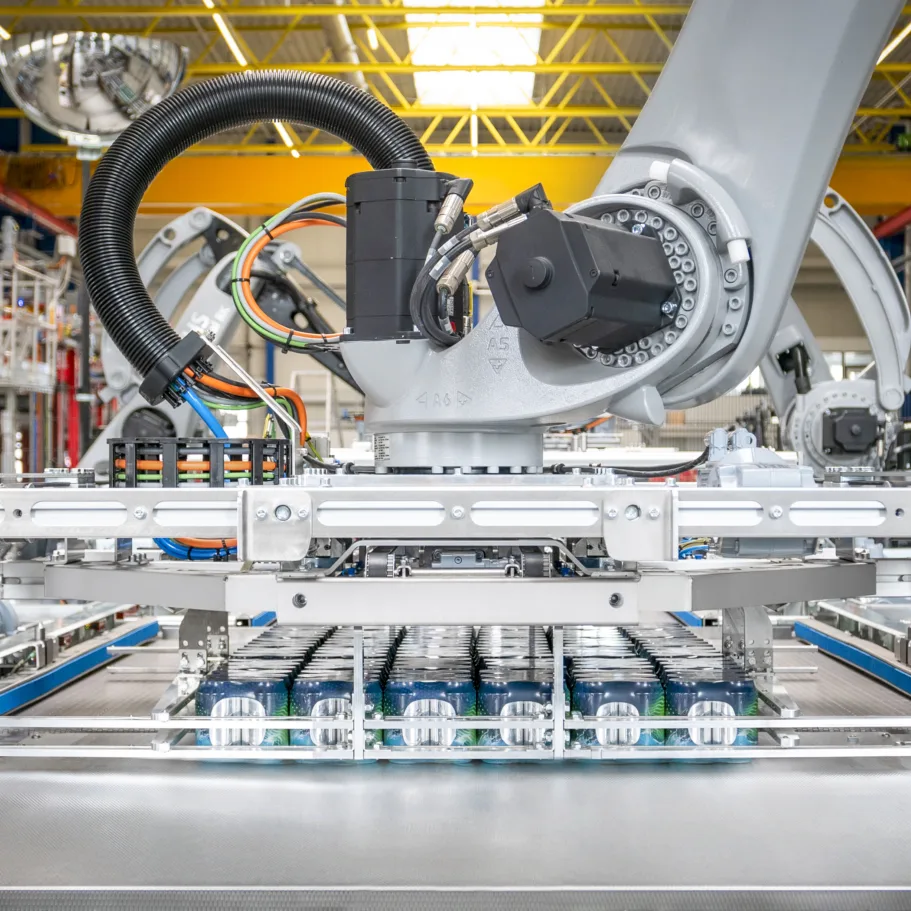

KHS invests in its plants outside Dortmund as well, such as here in Bad Kreuznach. Once the site of the Seitz-Werke, the plant now also has a modern technology center dedicated to filling and process technology which also serves as a training center for employees and customers.

The promise to create focused manufacturing centers and standardize products was kept to in the wake of the integration, however. Where to date the companies had offered more or less similar ranges of products, redundancies now had to be removed to prevent the two production sites from manufacturing practically identical machines. Filling machine production was thus moved entirely to Bad Kreuznach, with the vast production shops and cranes in Dortmund proving ideal for the production of bottle washers and space-consuming tunnel pasteurizers. Labeling technology was now also supplied from a single source in the Ruhr. In the next few years the company focused on setting up a clearly structured portfolio without any overlaps. As a result of the merger entire departments of the former archrivals had to restructure and pool their expertise – a vast challenge which was in part assisted by external consultants.

The move to turnkey supplier

Klöckner was now able to show that the group meant business with its machine engineering division: through numerous mergers KHS rapidly made the move to turnkey supplier. In 1997 it procured the Karlsruhe Grässle company, an inspection technology specialist. Grässle produced what are known as “sniffers”: mass spectrometers which through air analysis determine what an empty returnable PET bottle was last filled with and whether it’s suitable for refilling. In 1999 the traditional Anker company from Hamburg was acquired. It made labeling machines for the low-to-medium capacity range, supplementing the existing KHS spectrum of high-performance machinery. At the turn of the millennium KHS entered the steel barrel washing and racking or keg technology sector with its purchase of GEA Till.

In 2003 the Dortmund company made its first explorations into PET aseptics by taking over Alfill and expanded its expertise in inspection technology with the acquisition of Metec. The highlight of this year was the integration of Kisters into KHS. The packaging machine manufacturer from Kleve – the worldwide market leader in its discipline – had already been part of Klöckner Mercator Maschinenbau for over ten years. The takeover of industry leader SIG Corpoplast, SIG Plasmax, both in Hamburg, SIG Moldtec in Essen and SIG Asbofill in Neuss was also something of a coup. With their expertise in PET stretch blow molding and barrier coating the two Hamburg companies were top in their field, with the Essen company experts in the manufacture of stretch blow molds and the Neuss branch specialized in aseptic filling.

After years of mergers, restructuring and expansion of the product portfolio and capacity adjustment KHS is now perfectly set up as a systems supplier and able to provide the beverage industry with turnkey plant engineering – a demand which the market increasingly makes of the company.