Beer metropolis in the Ruhr

Once upon a time Dortmund was almost the biggest city of beer in the world. With its turbulent history and vast number of breweries, of which only one still exists – plus one new microbrewery – it’s more than earned second place, however.

Dortmund’s brewing tradition goes back over 750 years. In 1266 a document issued by the Hanseatic town mentioned gruit ale for the first time, gruit ale being a medieval beer brewed with oats. This ancient brew didn’t draw its flavor from the oats, however, but from sweet gale or marsh Labrador tea, two shrubs which are also native to North Germany. Myrtle, rosemary, juniper, bay leaf, caraway seed and aniseed could also be added. The mixture had very little in common with today’s beer, either in taste or appearance, yet the thick, cloudy intoxicant was a success – perhaps thanks to the hallucinogenic properties of its ingredients.

At the end of the 13th century King Adolf of Nassau granted Dortmund the privilege to make beer; the taxes levied on the beverage helped the town to fill its coffers. When in 1332 Dortmund’s monopoly on beer was confirmed by Emperor Ludwig IV the city gained a secure, long-term source of income and prosperity. By the end of the 14th century sales of beer had already reached up to 2,400 tons per annum.

In 1517 a brewhouse at Krone am Markt was mentioned for the first time and just one year later the von Hövel family at the Hövel Hof on Hoher Wall was given the right to make beer. Shortly before this the German Purity Law had been passed in Bavaria which permitted only water, hops and malt to be used in Bavarian beer, thus lending the beverage a new quality. This was a genuine achievement for it not only improved the taste of beer but also meant that it kept longer. The exotic herbal mixtures of the Middle Ages thus soon also fell out of fashion north of the River Main and were gradually replaced by beer made with hops. This was not to everyone’s liking, however; in 1548 Dortmund’s town chronicler complained that “little is fine gruit beer brewed”. Nevertheless, the triumph of the new style of beer proved unstoppable. It was easier to transport and as a member of the Hanseatic League Dortmund had no trouble trading its new beer both within Germany and abroad.

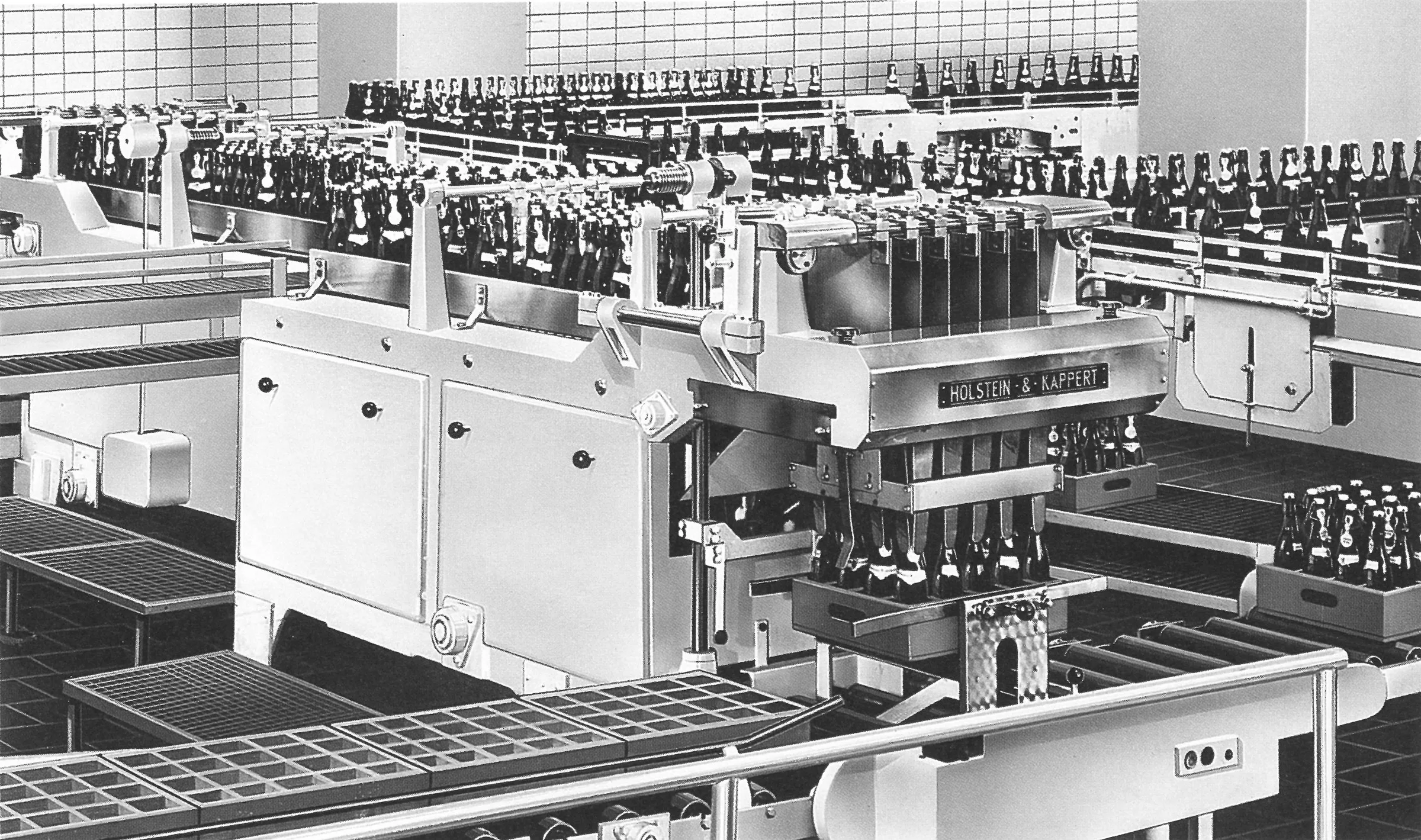

At the Dortmund Union Brewery beer bottles drop into their secondary packaging, a low-rim wooden crate, on a Holstein & Kappert drop-down packer.

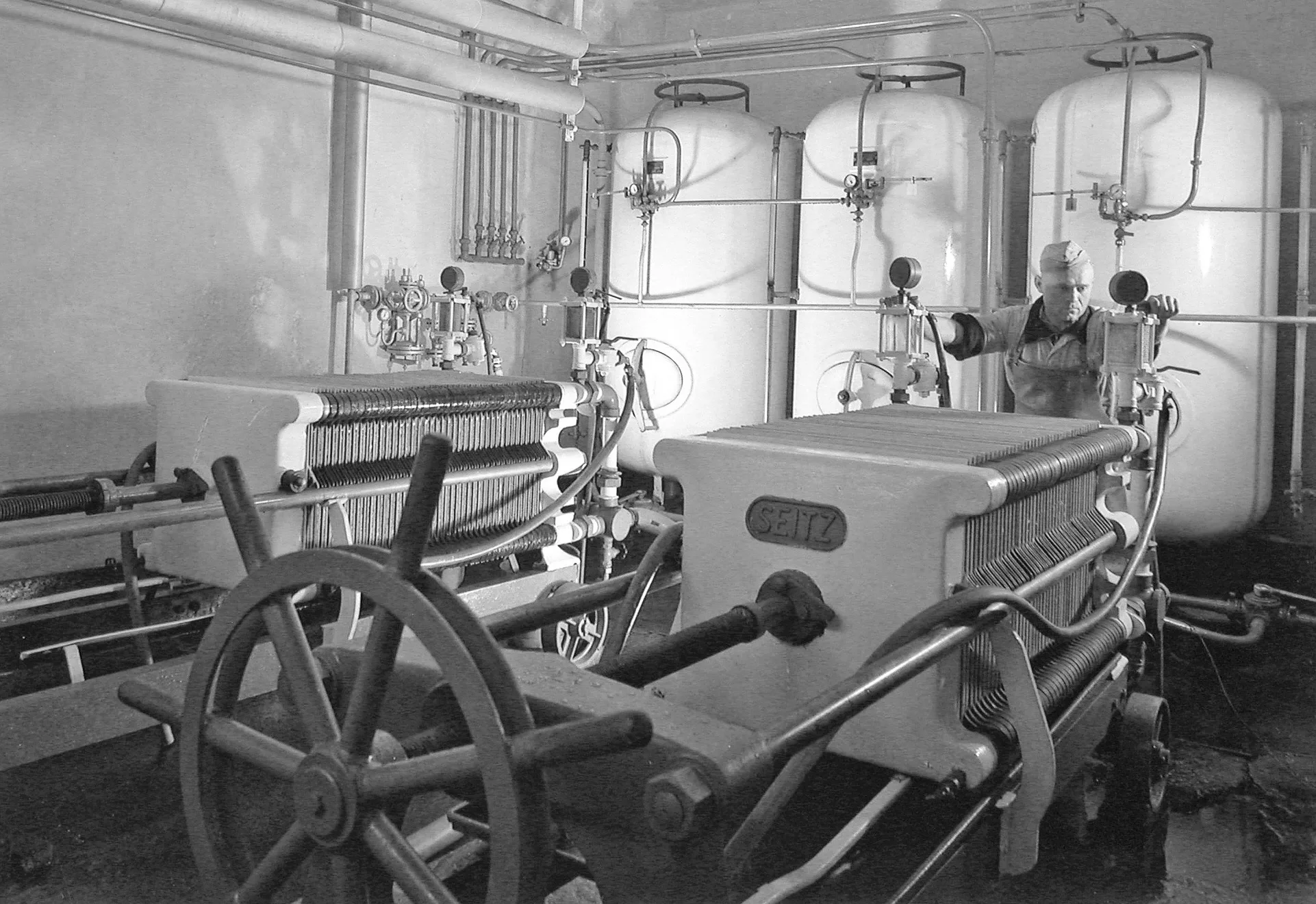

A Seitz-Werke sheet filter in use at Dortmund’s Thier Brewery at the beginning of the 1960s.

First mentioned in documents in 882 as Throtmanni, in the 13th and 14th centuries Dortmund – then known as Tremonia – was an important imperial free city and member of the Hanseatic League which had been granted the right to brew beer in 1293.

Hard times

In the wake of the Reformation and Thirty Years’ War the population in Dortmund had shrunk to a third of its former size by the mid-17th century. The town was hopelessly in debt; its fields and forests had been laid to waste and trade had come to a total standstill. Dortmund’s brewers found themselves having to cope with a long-term drop in demand. Protestant temperance and the devastating consequences of the war years were one problem; breweries suffered even more from their customers’ change in drinking habits, however. Overseas trade and colonialism had introduced new beverages, such as tea, coffee and cocoa, first making them popular and then affordable, and as a result there was a noticeable decline in the consumption of beer.

Things only started to change with the dawn of the industrial age. From the beginning of the 19th century Dortmund again started to flourish thanks to the mining of coal and processing of steel, gradually morphing into a center of industry. With the opening of the Cologne to Minden railroad in 1847 the town became the Ruhr’s main transport hub. About 50 years later the Dortmund-Ems Canal and the port opened, further championing the town’s economic development. Dortmund was well on its way to becoming a major city.

An advertising poster from the early years of the Dortmunder Actien-Brauerei, established in 1868 – then still active under its original name.

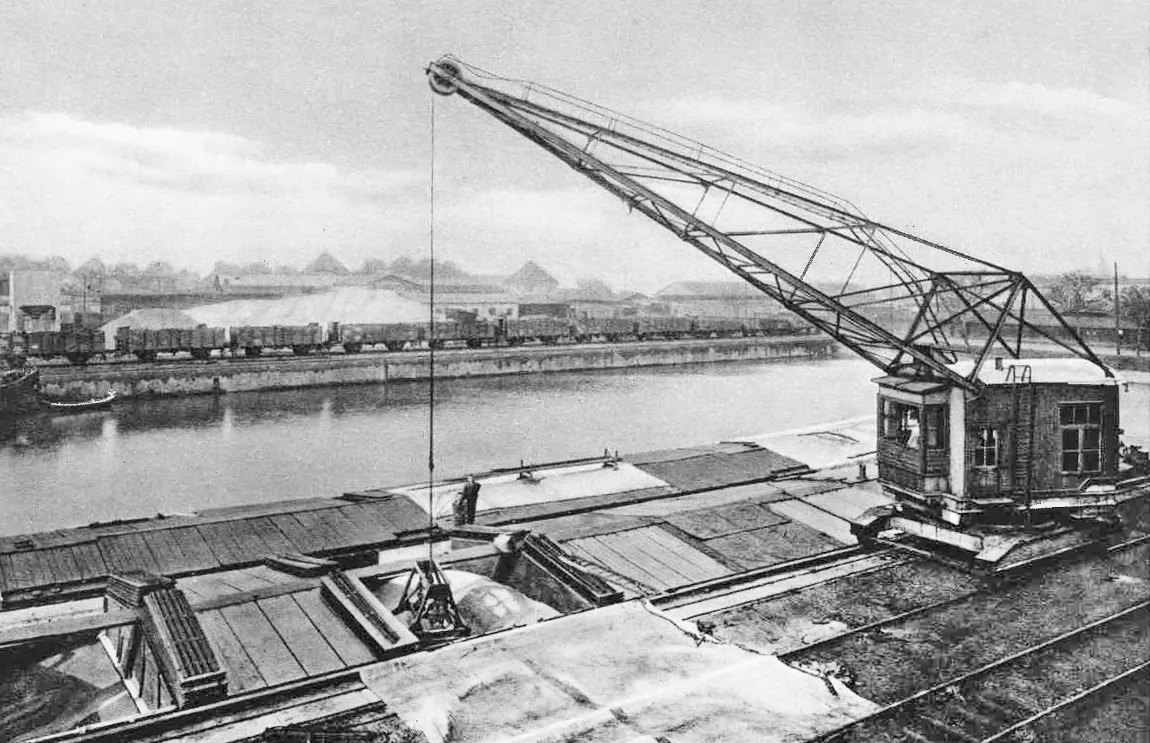

Unloading brewing barley at the docks in Dortmund, opened by Emperor Wilhelm II in 1899 and now the largest canal port in Europe.

In 1826 4,000 people still lived within the town ramparts in 940 houses with 453 barns and stables. The town was characterized by unpaved streets and alleys and had many half-timbered houses.

Export beer: a successful model

There were now 74 breweries in the Dortmund area, among them a number of traditional names such as Bergmann, Thier, Kronen and Stifts. For the first time bottom-fermented beer was brewed based on the Bavarian model – first dark beer, then light beer and later still Pilsner. In the first decades of the 20th century Export beer initially destined for countries outside Germany was developed which also proved successful back home in its own right.

In 1868, the year in which Holstein & Kappert was also founded, three Dortmund businessmen and a master brewer joined forces to form the Herberz & Co. brewery. A little later they turned their company into a corporation, renaming it Dortmunder Actien-Brauerei. Business was good, also abroad, and in 1881 Professor Carl Linde personally oversaw the installation of one of the first refrigeration machines he had developed, precipitating the ultimate triumph of light, bottom-fermented beers brewed in the Bavarian style which required a controlled maximum fermentation temperature of 10°C and could now be made all year round. In the meantime the Dortmund Union and Ritter breweries, two more major beer brands, had also set up shop.

Dortmunder Helles, light beer from Dortmund, was a hit – but the new technology was expensive, with only the big breweries able to afford Linde’s refrigeration system. Small breweries were forced to close or were sold. In 1895 there were just 28 breweries left in Dortmund, with a process of consolidation having set in which was to have consequences for the future of brewing in the city. Between 1920 and 1927, for example, the Union Brewery acquired all the equipment from the neighboring Germania Brewery and erected various new buildings on its own limited premises, including, in June 1927, the first high-rise block in Germany which was chiefly used to ferment and store beer. In 1968 the tower gained its four-sided, 9-meter-high, illuminated golden U which still lends the edifice its name of Dortmunder U today.

Dortmund Export has an original gravity of 12% to 14% and an alcohol content of usually a little over 5% by volume. It’s golden yellow in color and has a strong malty, slightly sweet taste.

Five questions for Dr. Heinrich Tappe, curator of the Dortmund Brewery Museum

How has the significance of beer changed through the ages?

In the Middle Ages beer was an everyday beverage and staple food. People didn’t drink water but small or weak beer – three or four liters of it per day. The strong beers of the time were reserved for special occasions and wealthy customers, such as the nobility and merchant classes. It wasn’t until beer was produced industrially at the end of the 19th century that it became a beverage drunk for enjoyment. Over the last 50 years the range of alcoholic and non-alcoholic beverages on offer has grown larger and larger, permanently weakening beer’s position on the market.

What caused the per capita consumption of beer in Germany to quadruple between 1950 and 1980? And why has this dropped by a third since?

The mass post-war eating binge of the 1950s and 1960s in Germany was accompanied by a binge on beer, with consumption rising to an unprecedented 150 liters per person. From 1975 this stagnated because alcoholic beverages were banned in companies, legislation toughened up on the alcohol limit for car drivers and beer was facing increasing competition from soft drinks – especially mineral water. The present sharp fall in consumption is the result of an increase in health awareness and the change in our demographics: the target group of potential beer drinkers aged between 16 and 50 is shrinking while the number of older people who don’t want to or can’t drink as much alcohol as they perhaps used to is rising.

What do you think are the greatest technical achievements in the brewing industry?

Maybe the refrigeration system of 1870 which enabled the fermentation and storage temperature to be controlled; and also the saccharometer developed in the mid-19th century which could be used to measure and influence the extract content of the beer wort. And, finally, without the knowledge of microbiological yeast it’d be practically impossible to offer beer of consistent quality today.

What makes Dortmund of all places the beer capital of Germany?

At the beginning of the 19th century the town had become a transport hub with its long beer-making tradition and was well on the way to becoming a major industrial stronghold. New breweries were conceived as big businesses which were designed to not only supply the city itself but also the entire emerging Ruhr region. Up until the 1970s the rest was one huge success story.

What can visitors to the Dortmund Brewery Museum expect?

Besides outlining the historical production of beer and the story of brewing in Dortmund we also explore the cultural history of beer which includes aspects such as advertising, club activities and the hospitality trade. The highlight of our collection is a Krupp beer delivery truck from 1920, only 22 of which were built.

At the Hansa Brewery new wooden barrels are branded with the company “brand” name by hand with the help of a branding iron.

A Phoenix hot and cold filling machine from “local matador” Holstein & Kappert in use at the Dortmund Stifts Brewery in c. 1959.

The Dortmunder U, a center for creativity and the arts, has housed the Museum Ostwall, Dortmund’s collection of 20th-century art, since 2010. Other tenants include the university of applied sciences and Dortmund’s Technical University.

Beer capital of Europe

In the 1950s and 1960s beer in the Ruhr was the common denominator for the hard-working men in the coal and steel industries. At the end of an arduous shift the miners and smelters had to compensate for the loss of fluid, with the demand for beer accordingly huge. In 1972 the brewing industry in Dortmund employed almost 6,000 people; with 7.5 million hectoliters produced a year Dortmund was the unrivaled beer capital of Europe, with Milwaukee in the USA the only place in the world where more beer was brewed than in the North Rhine-Westphalian city. The market share of Export was at about 60% in Germany, as opposed to pilsner which didn’t even manage to notch up 20%. Over two million hectoliters were brewed at the Dortmund Union Brewery alone, with the Dortmunder Actien-Brauerei or DAB producing 1.6 million hectoliters.

In the 1980s the continuing decline of the coal and steel industries also caused beer sales to plummet. The big breweries grew ever larger through mutual acquisition. In time, the facilities in the center of the city became too small; after taking over the Hansa Brewery in 1982, DAB moved to new premises at its established site on Steigerstrasse. The “brewery quarter” on Rheinische Strasse now only comprised the Union Brewery. In 1987 Kronen absorbed Stifts Brewery; a year later Union-Schultheiss (the Dortmund company had merged with the Berlin brewery back in 1972) turned into Brau und Brunnen which through further procurements was to become the biggest beverage group in Germany.

Dortmund trinity: Coal – steel – beer

“Seven million hectoliters of beer have to be brewed to mine seven million tons of hard coal and produce seven million tons of steel.” This was how the local vernacular once described the Dortmund trinity, the three traditional pillars of industry to which the city owed its economic boom up until into the 1970s.

In order to understand the prosperous position Dortmund held at the beginning of the 20th century, it helps to take a look at a few figures. In 1913 the amount of coal mined in Dortmund had reached 12.2 million tons, with coke production at 3.4 million tons – quantities which were barely exceeded even in later years. At the time production in the steel industry was quantified as follows: “In the north of the city [is] the Hoesch iron and steelworks whose production is sufficient to pay for Germany’s entire rye import with the proceeds; in the south [is] Hörder Verein, whose production of finished goods fills about ten long railroad trains pulling 50 cars apiece every day; and in the west [is] the Dortmund Union, whose annual production of rails would build a railroad track from North Cape to Constantinople.” The amount of beer output by Dortmund’s breweries rose exponentially between 1870 and 1913 from 140,000 to 1.7 million hectoliters. There’s thus no denying that even then Dortmund was one of the biggest producers of beer in the world.

Just a few years after the end of the Second World War Dortmund had become an economic eldorado: while the rate of unemployment in the Federal Republic was a high 10.1% in 1953, in North Rhine-Westphalia it was much lower at 4.9%, with just 2.3% without work in Dortmund – a figure at which we speak of de facto full employment.

A while later, however, circumstances and markets changed so drastically that the decline of the region’s leading coal, steel and beer industries simply couldn’t be stopped. In the 600,000-strong metropolis over 80,000 jobs were lost, with the unemployment rate up to 16% by the mid-1970s. Software, logistics and microtechnology now make up the new Dortmund trinity.

Increasing consolidation

The list of mergers is practically endless: in 1992 Kronen also took over Thier. In 1994 Union acquired Ritter and moved its production site from downtown Dortmund to the suburb of Lütgendortmund. Two years later DAB purchased Kronen which had been under the ownership of the Wenker family since 1729. Not much later its production facilities were also moved to Steigerstrasse. Following further mergers, when in 2004 Oetker subsidiary Radeberger also acquired not only DAB but also Brau und Brunnen, only one single site still producing beer was left in Dortmund. In the same year the Dortmund Union Brewery was torn down, leaving only the famous U Tower standing. This was subsequently converted into an arts center to mark the Ruhr’s status as European Capital of Culture in 2010. In 2009 the Thier Brewery also had to make way for a modern shopping center between Westenhellweg and Wall Platz.

One glimmer of light currently illuminating Dortmund’s long history of beer has materialized purely by coincidence. On a whim, so to speak, in 2005 microbiologist Thomas Raphael purchased the now defunct DBB brand in an online database; the brewery founded by the Bergmann family in 1796 had ceased to exist in 1972. Two years passed before he was able to use the name. In a small brewery in Hagen the first batches of beer were then produced. Friends and acquaintances had to help out – both with the marketing and drinking of the new brew. When some while later Bergmann beer was served at a large party, an article about it was published in a local newspaper. The response was so overwhelming that in 2007, together with a friend who happened to be a management consultant, Raphael set up a limited liability company. It was another three years before Bergmann beer was again actually produced in Dortmund – which is when Raphael himself started brewing once a week in his 1,000-liter tank at a former foundry in the docks area. He experimented with the recipes until the product was able to satisfy even the most critical of taste buds: those of former employees of the traditional brewery.

Bergmann now sells four different beers: pilsner, Spezialbier (special beer), black beer and of course Export – even if this only accounts for 5% to 10% of sales. People’s taste in beer has changed since the end of the 1960s. The motto is still a traditional one, however, (“hard work, honest reward”) and stands for the authentic, unadulterated, down-to-earth taste associated with the Ruhr region.

The beer can be imbibed in a number of hip and trendy Dortmund pubs. The microbrewery doesn’t wish to compete with the big concerns, however, instead preferring to concentrate on its retail activities. Even so, in the meantime Bergmann has an output of over 5,000 hectoliters. On Hoher Wall, not far from the Dortmunder U, the brewery runs its own historical kiosk from the 1950s, one of the genuine “Trinkhallen” or refreshment stands so popular in Dortmund which now enjoys cult status among young Dortmunders and their guests.

Since 2017 the Bergmann Brewery has been making beer on a larger scale on the premises of the former Phoenix steelworks where the PHOENIX West technology and service center has arisen in the past few years – a successful sign of how, following the demise of its key steel, coal and beer industries, Dortmund has managed to reinvent itself.