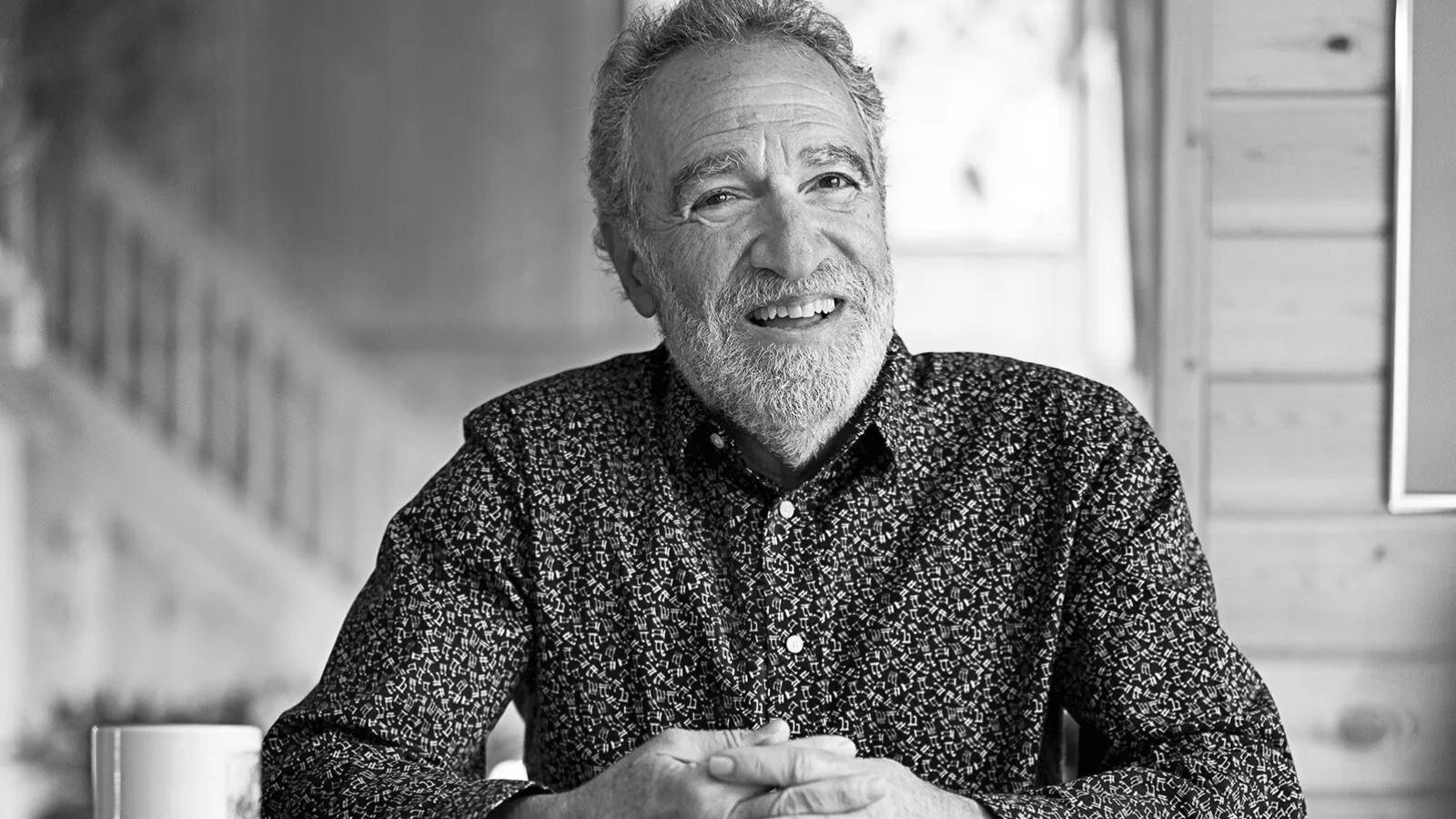

The father of homebrewing

At 71 Charlie Papazian is officially no longer working yet on the craft beer scene he’s still revered as something of a saint. We visit him in Boulder, Colorado, USA, to find out how, over the last 50 years, he’s established a trend which is still a triumph today.

As a nuclear engineer, how did you come to be interested in beer and brewing?

At the end of the 1960s/beginning of the 1970s I was studying at the University of Virginia in Charlottesville. Together with a few fellow students I met someone who made his own beer. Until then we’d never heard of people doing this themselves. We were curious – and this led us to make some interesting discoveries: the homebrew had character and tasted much better than the cheap brew we could afford as students and that I’d never really liked anyway.

And that prompted you to follow suit?

It did, yes. I had the recipe written down for me – six lines on a postcard. It took me three attempts to produce my first palatable beer. For us budding engineers it was both fun and exciting to put our scientific knowledge to practical use to a certain degree – and we had some respectable results. Soon, however, I was the only one left seriously pursuing this. I experimented and tried to make the beer better and better and therefore replaced the cane sugar with dextrose, for example, or baker’s yeast with real brewer’s yeast which back then wasn’t that easy to come by. At the university other groups of students also started brewing. Very early on we discovered that it was great fun to talk about our new enjoyment of beer. It was a really relaxed, friendly group that quickly gave rise to a kind of sense of community, both in Charlottesville and in Colorado, where I moved to in 1972.

How did you become the expert for homebrew that you are today?

Here in Boulder word soon spread that I knew how to make beer. I was asked if I wanted to teach it and so I gave courses in homebrewing for a total of ten years. During this period I of course also learned a lot myself and continued to build up my expertise. There were hardly any books on the subject around at the time so I wrote my own six-page pamphlet that I could hand out to the people on my courses. Over the years more and more information was added to it until I’d written an entire book, the forerunner of ‘The Complete Joy of Homebrewing’ which has sold about 1.5 million copies in the last 35 years.

Where did the inspiration to start experimenting with flavors come from?

One particular source of inspiration was British writer Michael Jackson who published his ‘World Guide to Beer’ in 1977. This was where I first became aware of the existence of things like fruit beers, lambic* or other exotic beers. My friends sometimes brought a selection of beers back from their trips to Germany or Belgium, such as pilsner, light beer or Rauchbier [smoked beer] from Bamberg. Talking about beer together was of course also a big thing. We were a bunch of crazy people who tried out all kinds of things and infected one another with our enthusiasm and curiosity. We used whatever ingredients we liked, putting lemon grass tea, orange peel, chocolate, chili peppers or cloves in our beer, to name but a few examples.

* Lambic = a Belgian specialty beer (also lambiek) made by spontaneous fermentation.

How has brewing affected your life?

For me, what was just a hobby soon became a vocation that has influenced my entire life. And vice versa, with my passion and through my mission I’ve had a great impact on my environment. The sentence I hear most often throughout the entire country is, “Thanks for your book, Charlie. It changed my life.” It doesn’t matter whether my readers have stuck to homebrewing, become craft brewers or started up in the beer business. My motto of “Relax, don’t worry and have a homebrew” has shown them that they can achieve something they didn’t think possible and be successful with it. I’m proud that for about 95% of all craft brewers in the USA the starting point of their career was either one of my courses or my book.

Can you remember when and where the term ‘craft beer’ first cropped up?

The term first appeared in an article in our organization’s magazine ‘The New Brewer’ in the early 1990s. I liked the word and then often used it in my own publications, therefore presumably making sure that it established itself as a generic term. Before we’d only talked about microbreweries whose maximum output was specified as being 5,000 barrels** a year. This limit first rose to 10,000 and then to 15,000 barrels, thus keeping pace with the rapid development. If a brewer makes more than this, however, he or she then has to completely change the business model as regards premises, technology and logistics, for instance. From this size upwards we then speak of regional breweries. However, they all share the name of craft brewery, with this term standing for a certain philosophy and specific image, almost like a brand.

* * Barrel = 31.5 US gallons or 119.2 liters.

During his long career as the father of homebrewing Charlie Papazian has won countless awards.

»It’s taken a long time to create an awareness for the quality, variety and taste of beer.«

Charlie Papazian, the father of homebrewing and craft beer, founded the festival in 1982, with the first event limited to just 22 exhibitors.

In the USA craft beer has long been a separate industry which in some cases involves huge companies with a vast beer output. How do you see this development?

I prefer to use the word ‘community’ in conjunction with craft breweries. For me, ‘industry’ refers more to the big international brewery groups. These don’t communicate with one another but instead see themselves as rivals. One key point among craft brewers is that you help each other out. You’re not so much in competition with one another as with other categories of beverage. It’s taken a long time to create an awareness among consumers for quality, variety and taste. To have done this has really bonded us as a community.

Living legend

Nuclear engineer Charlie Papazian has made a name for himself way beyond the boundaries of the USA as a homebrewer and best-selling author (‘The Complete Joy of Homebrewing’). In 1978 he founded the American Homebrewers Association and one year later the Association of Brewers. In 2005 this merged with the Brewers Association, of which Papazian was president until 2016. Each year Papazian presents the awards at the Great American Beer Festival in Denver and at the World Beer Cup which takes place every two years. The 71-year-old is an enthusiastic gardener and successfully grows hops on his land. As a passionate cook he is also the initiator of National Pie Day which is celebrated on his birthday, January 23.

How have beer drinking habits changed since the 1970s?

A lot of things in our culture have changed since then. The whole concept of local and regional products, for example, or the fact that more and more people are recognizing the added value provided by high-quality foods. There’s also the general increase in wealth, allowing a growing number of consumers to afford better products. This development is at various stages in the different countries of the world. In the USA, we’re very advanced in this respect as regards beer. In Germany, where the German Purity Law still carries great weight, I think people have to learn to appreciate the value of diversity more. Then you’d create more freedom for experiencing and enjoying new beers – and gain new target groups. I travel a lot in Japan, Southeast Asia and parts of Latin America. The craft beer scene there may be small but it’s absolutely lively.

What’s stopped you from making and selling your beers on a grander scale?

When you set up a company, it’s no longer just about making beer. You have to manage people. I’m good at this but it’s not my favorite job. I know a whole bunch of craft beer colleagues who regret having becoming entrepreneurs and miss the actual brewing. Moreover, I didn’t want the pressure of having to sell my own products. In the 1970s you earned $60 a barrel. Compared to now, where $600 to $800 per barrel are realized in a craft beer taproom, this was extremely little – and no basis for a successful business model.

Papazian’s collection of trophies includes Charlie 1981 (center) from a series of beers a brewer inspired by Papazian once dedicated to him.

Would you say that the craft beer movement has influenced the big industrial brewery groups?

Oh yes! At the latest in the 1980s when Miller launched a stout to market and a little later a competitor a honey lager, I realized that the big names had understood that craft beer wasn’t just a one-day wonder. Nowadays, the various groups’ pilot breweries are probably trying out all the same things their craft beer colleagues are experimenting with but presumably the marketing departments stop the results from reaching the supermarket shelves. Their business models are of course geared towards mass production and brewery groups can’t afford to dilute their product portfolios with their own craft beer brands. They’ve thus started buying up craft breweries in order to exploit their market potential and at the same time attempt to counter the drop in price for their premium brands.

How will beer change in the next ten to twenty years?

There are so many innovative, special beers around now that it’s sometimes hard to come by a Munich Helles, a totally normal IPA*** or a British ale. These more traditional beer styles, which the craft beer movement is actually originally based on, will make a comeback and present us with uncomplicated, drinkable quality beers. The number of breweries will also continue to grow in the future because the business model of the small, independent brewery works. Smaller craft breweries especially won’t see themselves as a brand so much but instead more heavily reflect their environment and the community they belong to as a mark of distinction. And, finally, packaging will be optimized further to minimize oxygen pickup, for instance. This is undoubtedly one of the reasons why there’s a current rise in the number of cans being filled, with this number certainly increasing in the future, too.

*** IPA = India Pale Ale, a light, stronger pale ale with an alcohol content of 6–9% by volume.

What’s the next big thing after craft beer?

Your question seems to suggest that the phenomenon of craft beer is coming to an end; I’m positive that the opposite is the case here! In the USA we’re primarily trying to stop consumers downing one soft drink after another. In keeping with the mega health trend many brewers are therefore trying to produce alcohol-reduced, alcohol-free or low-calorie beers. This is nothing new in Germany, but here in America this is still in its infancy. What’s more, the new flavored seltzers**** are very big at the moment, especially with breweries that use this to utilize their excess capacities generated during a boom. Personally, however, I’m neither a big fan of this nor of non-alcoholic beer.

**** (Hard) seltzer = an alcoholic yet relatively low-calorie beverage which contains carbonated water, about 5% alcohol (from fermentation) and often has a fruit flavoring.

How does the art of brewing vary from one region to another?

On my travels I notice time and again that many countries don’t have a beer culture at all, let alone understand anything about the art of brewing. As a result, most of the beer sold is cheap and insipid without any character of its own although there’s actually huge market potential for taste and variety. This isn’t only the fault of the unknowing consumer, however, but also often the result of laws that favor big conglomerates. In Thailand, for example, you can only obtain a brewing license if you produce vast amounts of beer. You can’t legally make beer on a small scale here. Small Thai brewers thus make their beer in Laos or Cambodia and then bring it back into their own country – an absurd situation.

»The more traditional beer styles will make a comeback and present us with uncomplicated, drinkable quality beers.«

Homebrewer and author

What’s inspired you the most?

When making beer I try to remember the very special experiences I’ve had in places like Germany, Belgium, England or Asia. Once I made a light pilsner, for example, which reminded me of an afternoon in the 1980s I spent under chestnut trees in a Bavarian beer garden. Or I make a dark lager which takes me back to U Fleku, a historic brewhouse in Prague that I’ve often been to. Or an Irish stout that I associate with a trip to Dublin.

Have you ever really messed up a beer?

Yes! Of course I’ve also made mistakes and the beer’s then spoiled. I’ve also made well-crafted beers which I then simply didn’t like. I once made an imperial stout, for instance, which was pretty sour. Although sour beers were becoming popular at the time, I’m not a great fan of them unless the overall taste is balanced. I’d hoped that other people might like my stout. I didn’t find enough people who did, however (laughs), and sadly then had to throw the beer away.

Would you tell us what your favorite beer is?

As a rule I can say that I always like local beers the best. Beer tastes best when it’s really fresh. I’ve experienced this in thousands of breweries. Even when you visit a brewery that doesn’t have such a good reputation, the beer there will undoubtedly taste great anyway because it hasn’t been transported. On the other hand, I’ve also drunk well-known brand beers all over the country which have tasted old and oxidized. This isn’t usually the breweries’ fault but because the product wasn’t cooled during transport – or sold in beverage stores that could double as a beer museum.