About 50 years ago the story of a very special type of beverage packaging began in Hamburg, now the home of KHS Corpoplast. This was when and where the first plastic bottles were blown which in the 1980s were to embark on an unparalleled march of triumph across the globe. Popular with consumers for their low weight and unbreakability and valued by companies as an economical alternative to the glass bottle, ecologically speaking the PET container is not without its critics. Reason enough, then, for “KHS competence” to talk to three experts about a container which has constantly evolved – and thus has many years of service still left in it.

“PET had all the advantages which allowed it to be used to make extremely light bottles.”

Mr. Seifert, what made you want to develop and market stretch blow molding machines for plastic bottles 50 years ago?

SEIFERT: Back in the 1960s my then employer Heidenreich & Harbeck made wood processing machines, particularly for the production of veneers. With the emergence of plastic surfaces and in view of cheaper competition from outside Germany the market was becoming rapidly more difficult so that we started specifically looking for totally new areas of business, including in polymer processing. In a small team we thus concentrated on plastic bottles for large filling quantities: initially for beer, which alongside coffee and mineral water was the main beverage at the time.

What ultimately caused the breakthrough?

SEIFERT: At the start of 1968, following our first experiments with PVC we filed a patent for the manufacture of bottles made of thermoplastic synthetics. Later, DuPont, one of the biggest chemical groups in the world from the USA, offered us a new material: polyethylene terephthalate, or PET for short, for which DuPont had secured itself a patent for its use in plastic bottles in 1970. It was far superior to PVC, among other things because it solidified much more easily. This material had all the advantages which still allow it to be used to make extremely light bottles with outstanding properties.

Was PET a completely new material then?

SEIFERT: No, PET was already being used in vast quantities in the textile industry. For our purposes, to put it simply all we had to do was get the molecules to form a different chain length.

And how were bottles then made from the PET material?

SEIFERT: DuPont isn’t a machine manufacturer. They therefore had our American competitor Milacron and us set up two machines in parallel – with a wall between them so that the one party couldn’t see what the other was up to.

Were these PET bottles the first plastic bottles on the market?

SEIFERT: At that time there weren’t any plastic bottles for carbonated beverages – whether for beer, soda pop or sparkling mineral water. PVC bottles were then in common use for still water in France, for example. But unlike ours these weren’t hardened and thus didn’t satisfy the requirements carbonated beverages make of containers regarding the high internal pressure.

Which market segment was the first to jump on the bandwagon?

SEIFERT: Beer was the first application we had in mind. The breweries we talked to weren’t averse to the idea but skeptical. In the USA, however, we soon realized that the beer industry wasn’t interested. In the end it was Pepsi-Cola which was the first brand to enter the market with a PET bottle.

“On-the-go purchases are a massive trend, as a result of which containers are getting smaller and smaller.”

How many of the first-generation Corpoplast machines still exist?

WIESE: All of them, actually: the rotary machine, the heater with infrared radiation, albeit in a modified form, the simultaneous blowing and stretching process. The basic principles are still the same – if now extremely polished.

SEIFERT: Compared to our original figures, the sheer increase in output alone is something we couldn’t possibly have envisaged back then. By 2003 the capacity was 1,800 bottles per cavity and hour and now we’re at 2,500. Or look at the bottle weight: our first 48-ounce bottle in the USA – that’s about 1.5 liters – then weighed about 60 grams. At the moment our sparkling water bottles of this size weight 24.5 grams – less than half. The savings in materials are just as considerable.

When did the environmental debate on the PET bottle begin?

SEIFERT: There was a lot of resistance to plastic bottles right from the beginning. Environmental campaigners wanted to prevent a marked increase in the percentage of non-returnables and were largely supported by the glass industry who advocated the use of returnable glass bottles for obvious reasons. Interestingly, at the time nobody mentioned that many of these bottles only achieve a small percentage of their circulation frequency due to the sensitive threaded necks. PET is favorable because no other material can be so easily recycled. However, the entire recycling chain first had to be set up and it took a while before the value of the used bottles became clear.

WIESE: The empty PET bottle is a very valuable raw material. The more expensive crude oil becomes, the more sense it makes to make sustainable use of this raw material by recycling the bottles.

What recycling rates does the PET bottle have and what is its ecobalance like compared to glass bottles?

WIESE: In Germany we now have a bottle-to-bottle recycling rate for PET of over 95%. This means that almost all the bottles used by us are turned back into bottles within Europe. Last year the German Environment Agency confirmed for the first time that the ecobalance of the non-returnable PET bottle equaled and in some categories even exceeded that of the returnable glass bottle with regard to its lower weight, increased percentage of recyclate and shorter distribution paths. Other countries haven’t quite reached this stage yet. Take the USA, for example: here, there’s very little bottle-to-bottle and more bottle-to-fiber recycling, where the PET ends up in the textile industry – at a rate of up to 40% as far as I know.

How has critical public awareness of PET changed?

WIESE: In Germany specifically there are two hot topics of discussion at the moment. Firstly, there are consumers who only drink from glass bottles because they have a totally unsubstantiated fear that chemicals could migrate from the plastic bottle to the beverage – which they would then consume. The second big issue is marine litter: the pollution of our oceans by plastic. China, Indonesia, the Philippines, Vietnam and Thailand are responsible for over 50% of this, five countries where prosperity and the economy are rapidly growing but waste disposal concepts are lagging behind. In these countries there’s unfortunately been little discussion of the plastic waste in the ocean to date; this subject is normally most talked about where the least waste is generated.

Where do you see the most areas of potential growth for the PET bottle?

WIESE: The dairy sector is becoming increasingly important in conjunction with PET. The biggest growth market, however, is definitely water – and not in Europe but in Africa and the entire southern hemisphere, where the water supply is becoming worse and worse and you can no longer drink the tap water. In China people are even using water tapped from 50-liter containers to wash dishes.

“The PET bottle has always been much better than its reputation.”

What demands do beverage producers and consumers make of a modern bottle – also regarding brands?

WIESE: For manufacturers the prime concerns are cost and aesthetic and functional requirements. The product must run through the line without any problems and reach the supermarket in perfect condition.

SCHULTE: So that I purchase a bottle as a consumer, it must be less of a container and more of a product experience. I expect something quite different from a top brand than I would from a discounter product. However, it goes without saying that both should have good handling properties and offer effective product protection. Customers don’t even think about this as long as everything’s in order. Should this not be the case for some reason, this reflects all the more harshly on the brand. This is why these barely visible criteria are absolutely determinative for design engineers and bottle designers.

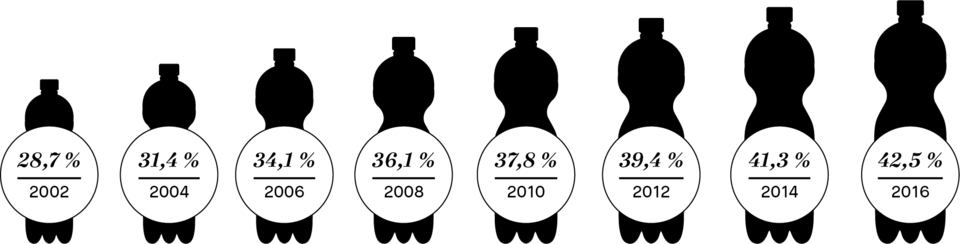

Share of all packaging from 2002 to 2016

Source: Euromonitor

Which consequences does this have for the bottle design and bottle shape?

SCHULTE: For an ultralight bottle I have to apply a very different design to the one used for a container which has a higher weight and greater stability. Here, I can play with different shapes. A lot of weight can be saved in the bottle neck in particular.

WIESE: Or you have to specifically provide more weight for a special design, for example for a shape which deviates from the cylinder and which only retains its shape under pressure when you increase the wall thickness.

SEIFERT: The ideal pressurized container would actually be a sphere ...

SCHULTE: But this is hard to stack (laughs). This brings us to a topic we haven’t talked about yet: logistics. For manufacturers this is a central issue: how many bottles they can store on a pallet and load onto a truck. This has to be taken into account in the design.

What makes a really good bottle in your opinion?

SCHULTE: When the consumer sees a bottle, he or she has to say “Wow! I want it!” This can vary from category to category, of course, and not only applies to the bottle shape but also the label – in other words, to the bottle as a whole.

SEIFERT: Whether it’s for a discounter or a high-end product, the bottle must always be consistently technically perfect.

WIESE (lacht): To put it a bit differently, a really good bottle has the KHS logo on its base.

What are the current trends regarding the various aspects of technology and design?

WIESE: Weight, ecology and costs are still the major concerns. These factors must be in perfect balance with the design; this is what’s expected of a bottle. As far as the bottle body is concerned, for instance, we’ve reached a limit regarding weight reduction. This is why we’re now thinking about the thread even if it will probably take some time before we can agree on new standards in this respect.

SCHULTE: From a designer’s point of view I always judge trends for the bottle as a whole – that is, including the label. For a long time we saw a trend towards the homemade where everything looked as though it had come from a small bottler or factory. Many are now distancing themselves from this with a totally reduced design. Another craze at the moment is for very imaginative, fairytale designs which tell a kind of story and where an entire world is built up around the product. Container shapes are gravitating towards the simpler, straight bottle.

WIESE: We mustn’t forget the various totally new product categories. On-the-go purchases are a massive trend which has a huge influence on the bottle size, with containers are becoming smaller and smaller.

Do you have specific expectations of the development of the bottle regarding digitization?

WIESE: Coca-Cola has created a benchmark in this field with the bottle which bears the name of the customer. This was a campaign which cost a lot of money but generated huge sales. A lot is bound to happen in this context. We’re seeing more and more personalized advertising and we’re sure to find this also reflected in packaging design.

SCHULTE: The role social media plays is interesting in this conjunction. Many designer bottles are being presented by young people on Instagram and Facebook shown holding a particularly stylish water. This is a level of communication which didn’t used to exist in this form and which we shouldn't neglect in the future, especially when we’re dealing with premium products.

How do you see the future of the PET bottle in the medium-to-long term? What can this learn from its past for the future?

WIESE: In the medium term there’s absolutely no alternative to the PET bottle. In the long term it’s already becoming apparent that new and lighter materials made from renewable raw materials will gain in significance; these will perhaps have even better barrier properties or improved hardening properties. A second, parallel flow of materials must be created for recycling purposes. We can see the first ideas for this on the horizon and in the long term this material could replace PET.

SCHULTE: What we can learn is to communicate much more intensively and much better with the consumer. The PET bottle has always been much better than its reputation; many facts are still not known to the customer today, however. I think it’s important that we shed light on new materials – in both a positive and negative sense. If we’d starting doing this with PET much earlier on, many problems could have been avoided.

SEIFERT: That’s right, but of course we now also know a lot more than we did back then.