On April 23 of this year German brewers in Ingolstadt celebrated the 500th anniversary of what’s allegedly the first food law in the world. When in her official speech German chancellor Angela Merkel mentioned craft brewers and their willingness to experiment, some of the functionaries present may have drawn a sharp breath. The rivalry between the hardliners among organized beer makers and some of the more rebellious craft brewers is so great and their positions so irreconcilable that some media are even currying favor among the public by talking about the “battle over the German Purity Law”. Verbal disarmament seems to be called for ...

Pure, purer, Purity Law?

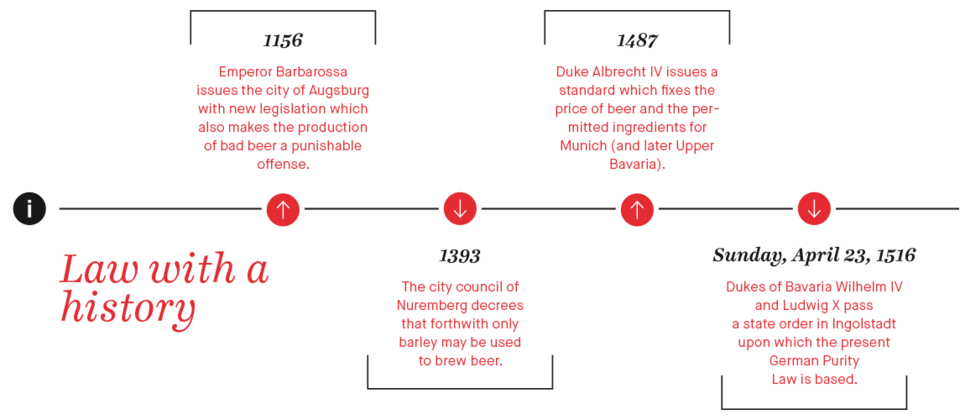

What does the famous law concern? Basically just barley, hops and water – for according to the then dukes of Bavaria a beer needs no more than this. However, in the past the regulation was never as irrefutable as the brewing industry now likes to suggest; firstly, barley soon became barley malt as people could brew better with germinated, dried barley. Secondly, wheat was soon also allowed to be used – otherwise there would be no wheat beer. Thirdly, a further factor was added in the 19th century: yeast, which was “somehow around” in the Middle Ages but totally unheard of as a designated ingredient. And fourthly, in time more and more additives found their way into beer, among them herbs, ginger, even potash, boiled fish bladder (isinglass), and calf’s trotters. The list of scurrilities would have been endless had the Bavarians not returned to the pure doctrine in the second half of the 19th century and begun to cement it in various laws. Finally, in 1906 they made their joining the German empire conditional on the Purity Law being applied throughout Germany.

While the major breweries still like to present the German Purity Law as some kind of consumer protection bill, the adherence to which is all that guarantees the high quality of German beer, its critics see it as an instrument which restricts the market – one which in the past isolated non-German beers and now anything which does not meet the industrial norm. Some people even talk about it being a “unity law” which has turned beer into little more than dishwater – both boring and lacking in any distinguishing features.

Good beer – bad beer?

In the 1980s, with the support of the German government, the German Brewers’ Association opposed the import of beers from other member states of what was then the EEC which were not made according to the German Purity Law. Through a major campaign the law was successfully anchored in the public consciousness as being synonymous with quality and non-German beers were branded “chemical beer” – an overstatement which many consumers still take as read. The ban on selling non-German brews in Germany which had not been made according to the Purity Law under the designation of “beer” was overturned by the European Court of Justice in 1987 as it contravened the EEC’s free movement of goods. The plea on the part of the Germans that health risks were being posed to German citizens was thrown out by the court; after all, the “suspect” additives in non-German beers were also permitted in other German foods.

The legal situation has grown no less complex since then. In 1993 the Weimar Republic’s Beer Taxation Law was replaced by a new regulation which separates food legislation and fiscal concerns regarding beer. However, firstly the regulation has included the word provisional in its title for 23 years now – and secondly it has created a situation whereby a brewer is still taxed for a beer which may neither be sold within nor outside Germany.

Certain additives and ingredients are also now officially allowed: in bottom-fermented beers, such as lager or pale ale, only barley malt, hops, yeast and water may be used as in the past, but top-fermented beers, such as “Altbier, Kölsch” or wheat beer, which actually only differ from the aforementioned in the type of yeast used, may also contain malts from other grains, sugar and coloring. This all seems rather illogical. Exceptions to the strict rules are admissible but only if they are recognized by the federal state authorities as “special beer” within the law – and if the brewer pays for this special dispensation.

Brewing tradition or consumer health

Only since a Saxon brewery successfully contended a dispensation such as the above before the Federal Administrative Court in 2005 have permits been granted more freely. The German Purity Law serves to uphold tradition and not to protect the health of the consumer, ruled the court, and the regulation interferes with the brewer’s professional freedom. Upholding a tradition does not justify outlawing all deviations from it as “inferior, false (adulterated) or even dangerous beer”.

To this very day, however, the court’s decision has failed to impress the Free State of Bavaria; it’s the only German federal state to consistently refuse to issue the exception permit for special beers allowed for by German law. And it goes even further: beer which has already been made is not given a shelf life by the Bavarian Federal Office for Health and Food Safety, meaning that in the past entire batches have had to be destroyed.

Contradictory purity

It’s understandable that craft breweries find this policy incomprehensible. How can it be that the so sacrosanct German Purity Law prevents traditional beer styles from being brewed but allows substances such as polyvinylpolypyrrolidone (PVPP) or diatomaceous earth to be added to beer to refine it and admits that these are not completely removed from the beer? Why does the German Purity Law promote naturalness on the one hand yet allow hop extract dissolved by hexane or methyl chloride to be used instead of fresh hop cones on the other? Purists are even bothered by the fact that beer is allowed to be physically “mishandled” by pasteurization which may not affect a person’s health but turns the brew into a dead preserve. Finally, it appears questionable why a regulation prohibits the addition of coriander or orange peel to lend the beer a particular note but does not protect beer from glyphosate residue – however minute this may be.

The fact that the beer law is frequently adapted to suit the requirements of the big breweries causes much headshaking among creative brewers – with one most recent amendment permitting the launch of mixed beer beverages to market which German brewers warmed towards surprisingly quickly after much initial lamentation. Some craft brewers are now demanding that the German Purity Law be replaced by a law of naturalness. It’s interesting to note in this context that the majority of German craft beers actually don’t conflict with the German Purity Law.

Final agreement?

It’s obvious that there’s still much to be done. Even the Bavarian Brewers’ Association doesn’t dispute this which, faced with a steady decline in beer output and a boom in the number of craft breweries, has long realized that a genuine return to variety, taste and quality could be a good way of encouraging future target groups to enjoy more beer. In any case, the debate on the German Purity Law has long since begun. It would certainly be helpful if there was less agitation as everyone agrees that they wish to distance themselves from the long list of additives which European law allows. At the end of the day it’s all about legal security through the uniform application throughout Germany of a law which was made with good intentions – and the time is definitely ripe for this now that its 500th anniversary has been celebrated.

Incidentally, at the official celebration the functionaries soon breathed a sigh of relief; the German chancellor restricted her praise of the innovative skills of craft brewers by adding, “... in observance of the German Purity Law”.